The Coach Builder

Prehistory

Some

horsecarts

found

in

Celtic

graves

show

hints

that

their

platforms

were

suspended

elastically.[4]

Four-wheeled

wagons

were

used

in

prehistoric

Europe,

and

their

form

known

from

excavations

suggests

that

the

basic

construction

techniques

of

wheel

and

undercarriage (that survived until the age of the motor car) were established then.[5]

Chariot

The

earliest

recorded

sort

of

carriage

was

the

chariot,

reaching

Mesopotamia

as

early

as

1900

BC.[6]

Used

typically

for

warfare

by

Egyptians,

the

near

Easterners

and

Europeans,

it

was

essentially

a

two-wheeled

light

basin

carrying

one

or

two

passengers,

drawn

by

one

to

two

horses.

The

chariot

was

revolutionary

and

effective

because

it

delivered

fresh

warriors

to

crucial

areas

of

battle

with

swiftness.

Roman carriage

First

century

BC

Romans

used

sprung

wagons

for

overland

journeys.[7]

It

is

likely

that

Roman

carriages

employed

some

form

of

suspension on chains or leather straps, as indicated by carriage parts found in excavations.

Ancient Chinese carriage

In

the

kingdom

of

the

Zhou

Dynasty

the

Warring

States

were

also

known

to

have

used

carriages

as

transportation.

With

the

decline

of

these civilizations these techniques almost disappeared.

Medieval carriage

The

medieval

carriage

was

typically

a

four-wheeled

wagon

type,

with

a

rounded

top

('tilt')

similar

in

appearance

to

the

Conestoga

Wagon

familiar

from

the

USA.

Sharing

the

traditional

form

of

wheels

and

undercarriage

known

since

the

Bronze

Age,

it

very

likely

also

employed

the

pivoting

fore-axle

in

continuity

from

the

ancient

world.

Suspension

(on

chains)

is

recorded

in

visual

images

and

written

accounts

from

the

14th

century

('chars

branlant'

or

rocking

carriages),

and

was

in

widespread

use

by

the

15th

century.[8]

Carriages

were

largely

used

by

royalty,

aristocrats

(and

especially

by

women),

and

could

be

elaborately

decorated

and

gilded.

These

carriages

were

on

four

wheels

often

and

were

pulled

by

two

to

four

horses

depending

on

how

they

were

decorated

(elaborate

decoration

with

gold

lining

made

the

carriage

heavier).

Wood

and

iron

were

the

primary

requirements

needed

to

build

a

carriage

and

carriages that were used by non-royalty were covered by plain leather.

Another

form

of

carriage

was

the

pageant

wagon

of

the

14th

century.

Historians

debate

on

the

structure

and

size

of

pageant

wagons;

however,

they

are

generally

miniature

house-like

structures

that

rest

on

four

to

six

wheels

depending

on

the

size

of

the

wagon.

The

pageant

wagon

is

significant

because

up

until

the

14th

century

most

carriages

were

on

two

or

3

wheels;

the

chariot,

rocking

carriage,

and

baby

carriage

are

two

examples

of

carriages

which

pre-date

the

pageant

wagon.

Historians

also

debate

whether

or

not

pageant

wagons

were

built

with

pivotal

axle

systems,

which

allowed

the

wheels

to

turn.

Whether

it

was

a

four-

or

six-wheel

pageant

wagon,

most

historians

maintain

that

pivotal

axle

systems

were

implemented

on

pageant

wagons

because

many

roads

were

often

winding

with

some

sharp

turns.

Six

wheel

pageant

wagons

also

represent

another

innovation

in

carriages;

they

were

one

of

the

first

carriages

to

use

multiple

pivotal

axles.

Pivotal

axles

were

used

on

the

front

set

of

wheels

and

the

middle

set

of

wheels.

This

allowed

the

horse

to move freely and steer the carriage in accordance with the road or path.

Coach

One

of

the

great

innovations

of

the

carriage

was

the

invention

of

the

suspended

carriage

or

the

chariot

branlant

(though

whether

this

was

a

Roman

or

medieval

innovation

remains

uncertain).

The

'chariot

branlant'

of

medieval

illustrations

was

suspended

by

chains

rather

than

leather

straps

as

had

been

believed.[9][10]

Chains

provided

a

smoother

ride

in

the

chariot

branlant

because

the

compartment

no

longer

rested

on

the

turning

axles.

In

the

15th

century,

carriages

were

made

lighter

and

needed

only

one

horse

to

haul

the

carriage.

This

carriage

was

designed

and

innovated

in

Hungary.[11]

Both

innovations

appeared

around

the

same

time

and

historians

believe

that

people

began

comparing

the

chariot

branlant

and

the

Hungarian

light

coach.

However,

the

earliest

illustrations

of the Hungarian 'Kochi-wagon' do not indicate any suspension, and often the use of three horses in harness.

Under

King

Mathias

Corvinus

(1458–90),

who

enjoyed

fast

travel,

the

Hungarians

developed

fast

road

transport,

and

the

town

of

Kocs

between

Budapest

and

Vienna

became

an

important

post-town,

and

gave

its

name

to

the

new

vehicle

type.[12]

The

Hungarian

coach

was

highly

praised

because

it

was

capable

of

holding

8

men,

used

light

wheels,

could

be

towed

by

only

one

horse

(it

may

have

been

suspended

by

leather

straps,

but

this

is

a

topic

of

debate).[13]

Ultimately

it

was

the

Hungarian

coach

that

generated

a

greater

buzz

of

conversation

than

the

chariot

branlant

of

France

because

it

was

a

much

smoother

ride.[13]

Henceforth,

the

Hungarian

coach

spread

across

Europe

rather

quickly,

in

part

due

to

Ippolito

d'Este

of

Ferrara

(1479–1529),

nephew

of

Mathias'

queen

Beatrix

of

Aragon,

who

as

a

very

junior

Archbishopric

of

Esztergom

developed

a

liking

of

Hungarian

riding

and

took

his

carriage

and

driver

back

to

Italy.[14]

Around

1550

the

'coach'

made

its

appearance

throughout

the

major

cities

of

Europe,

and

the

new

word

entered

the

vocabulary

of

all

their

languages.[15]

However,

the

new

'coach'

seems

to

have

been

a

concept

(fast

road

travel

for

men)

as

much

as

any

particular

type

of

vehicle,

and

there

is

no

obvious

change

that

accompanied

the

innovation.

As

it

moved

throughout

Europe

in

the

late

16th

century,

the

coach’s

body

structure

was

ultimately

changed,

from

a

round-top

to

the

'four-poster'

carriages

that

became

standard by c.1600.[8]

Later development of the coach

The

coach

had

doors

in

the

side,

with

an

iron

step

protected

by

leather

that

became

the

"boot"

in

which

servants

might

ride.

The

driver

sat

on

a

seat

at

the

front,

and

the

most

important

occupant

sat

in

the

back

facing

forwards.

The

earliest

coaches

can

be

seen

at

Veste

Coburg,

Lisbon,

and

the

Moscow

Kremlin,

and

they

become

a

commonplace

in

European

art.

It

was

not

until

the

17th

century

that

further

innovations

with

steel

springs

and

glazing

took

place,

and

only

in

the

18th

century,

with

better

road

surfaces,

was

there

a

major innovation with the introduction of the steel C-spring.[16]

It

was

not

until

the

18th

century

that

steering

systems

were

truly

improved.

Erasmus

Darwin

was

a

young

English

doctor

who

was

driving

a

carriage

about

10,000

miles

a

year

to

visit

patients

all

over

England.

Darwin

found

two

essential

problems

or

shortcomings

of

the

commonly

used

light

carriage

or

Hungarian

carriage.

First,

the

front

wheels

were

turned

by

a

pivoting

front

axle,

which

had

been

used

for

years,

but

these

wheels

were

often

quite

small

and

hence

the

rider,

carriage

and

horse

felt

the

brunt

of

every

bump

on

the road. Secondly, he recognized the danger of overturning.

A

pivoting

front

axle

changes

a

carriage’s

base

from

a

rectangle

to

a

triangle

because

the

wheel

on

the

inside

of

the

turn

is

able

to

turn

more

sharply

than

the

outside

front

wheel.

Darwin

proposed

to

fix

these

insufficiencies

by

proposing

a

principle

in

which

the

two

front

wheels

turn

about

a

centre

that

lies

on

the

extended

line

of

the

back

axle.

This

idea

was

later

patented

as

Ackerman

Steering.

Darwin argued that carriages would then be easier to pull and less likely to overturn.

Carriage

use

in

North

America

came

with

the

establishment

of

European

settlers.

Early

colonial

horse

tracks

quickly

grew

into

roads

especially

as

the

colonists

extended

their

territories

southwest.

Colonists

began

using

carts

as

these

roads

and

trading

increased

between

the

north

and

south.

Eventually,

carriages

or

coaches

were

sought

to

transport

goods

as

well

as

people.

As

in

Europe,

chariots,

coaches

and/or

carriages

were

a

mark

of

status.

The

tobacco

planters

of

the

South

were

some

of

the

first

Americans

to

use

the

carriage

as

a

form

of

human

transportation.

As

the

tobacco

farming

industry

grew

in

the

southern

colonies

so

did

the

frequency

of

carriages,

coaches

and

wagons.

Upon

the

turn

of

the

18th

century

wheeled

vehicle

use

in

the

colonies

was

at

an

all-time

high.

Carriages,

coaches

and

wagons

were

being

taxed

based

on

the

number

of

wheels

they

had.

These

taxes

were

implemented

in

the

South

primarily

as

the

South

had

superior

numbers

of

horses

and

wheeled

vehicles

when

compared

to

the

North.

Europe,

however,

still used carriage transportation far more often and on a much larger scale than anywhere else in the world.

Carriages

and

coaches

began

to

disappear

as

use

of

steam

propulsion

began

to

generate

more

and

more

interest

and

research.

Steam

power

quickly

won

the

battle

against

animal

power

as

is

evident

by

a

newspaper

article

written

in

England

in

1895

entitled

"Horseflesh vs. Steam".[17] The article highlights the death of the carriage as the means of transportation.

Nowadays,

carriages

are

still

used

for

day-to-day

transport

in

the

United

States

by

some

minority

groups

such

as

the

Amish.

They

are

also still used in the tourism as vehicles for sightseeing in cities such as Bruges, Vienna, New Orleans, and Little Rock, Arkansas.

The

most

complete

working

collection

of

carriages

can

be

seen

at

the

Royal

Mews

in

London

where

a

large

selection

of

vehicles

is

in

regular

use.

These

are

supported

by

a

staff

of

liveried

coachmen,

footmen

and

postillions.

The

horses

earn

their

keep

by

supporting

the

work

of

the

Royal

Household,

particularly

during

ceremonial

events.

Horses

pulling

a

large

carriage

known

as

a

"covered

brake"

collect

the

Yeoman

of

the

Guard

in

their

distinctive

red

uniforms

from

St

James's

Palace

for

Investitures

at

Buckingham

Palace;

High

Commissioners

or

Ambassadors

are

driven

to

their

audiences

with

The

Queen

in

landaus;

visiting

heads

of

state

are

transported

to

and

from

official

arrival

ceremonies

and

members

of

the

Royal

Family

are

driven

in

Royal

Mews

coaches

during

Trooping

the

Colour,

the Order of the Garter service at Windsor Castle and carriage processions at the beginning of each day of Royal Ascot.

Construction

Body

Carriages

may

be

enclosed

or

open,

depending

on

the

type.[18]

The

top

cover

for

the

body

of

a

carriage,

called

the

head

or

hood,

is

often

flexible

and

designed

to

be

folded

back

when

desired.

Such

a

folding

top

is

called

a

bellows

top

or

calash.

A

hoopstick

forms

a

light

framing

member

for

this

kind

of

hood.

The

top,

roof

or

second-story

compartment

of

a

closed

carriage,

especially

a

diligence,

was

called

an

imperial.

A

closed

carriage

may

have

side

windows

called

quarter

lights

(British)

as

well

as

windows

in

the

doors,

hence

a

"glass

coach".

On

the

forepart

of

an

open

carriage,

a

screen

of

wood

or

leather

called

a

dashboard

intercepts

water,

mud

or

snow

thrown

up

by

the

heels

of

the

horses.

The

dashboard

or

carriage

top

sometimes

has

a

projecting

sidepiece

called

a

wing

(British). A foot iron or footplate may serve as a carriage step.

A

carriage

driver

sits

on

a

box

or

perch,

usually

elevated

and

small.

When

at

the

front

it

is

known

as

a

dickey

box,

a

term

also

used

for

a

seat

at

the

back

for

servants.

A

footman

might

use

a

small

platform

at

the

rear

called

a

footboard

or

a

seat

called

a

rumble

behind the body. Some carriages have a moveable seat called a jump seat. Some seats had an attached backrest called a lazyback.

The

shafts

of

a

carriage

were

called

limbers

in

English

dialect.

Lancewood,

a

tough

elastic

wood

of

various

trees,

was

often

used

especially

for

carriage

shafts.

A

holdback,

consisting

of

an

iron

catch

on

the

shaft

with

a

looped

strap,

enables

a

horse

to

back

or

hold

back

the

vehicle.

The

end

of

the

tongue

of

a

carriage

is

suspended

from

the

collars

of

the

harness

by

a

bar

called

the

yoke.

At

the

end of a trace, a loop called a cockeye attaches to the carriage.

In

some

carriage

types

the

body

is

suspended

from

several

leather

straps

called

braces

or

thoroughbraces,

attached

to

or

serving

as

springs.

Undergear

Beneath

the

carriage

body

is

the

undergear

or

undercarriage

(or

simply

carriage),

consisting

of

the

running

gear

and

chassis.[19]

The

wheels

and

axles,

in

distinction

from

the

body,

are

the

running

gear.

The

wheels

revolve

upon

bearings

or

a

spindle

at

the

ends

of

a

bar

or

beam

called

an

axle

or

axletree.

Most

carriages

have

either

one

or

two

axles.

On

a

four-wheeled

vehicle,

the

forward

part

of

the

running

gear,

or

forecarriage,

is

arranged

to

permit

the

front

axle

to

turn

independently

of

the

fixed

rear

axle.

In

some

carriages

a

'dropped

axle',

bent

twice

at

a

right

angle

near

the

ends,

allows

a

low

body

with

large

wheels.

A

guard

called

a

dirtboard

keeps

dirt

from the axle arm.

Several

structural

members

form

parts

of

the

chassis

supporting

the

carriage

body.

The

fore

axletree

and

the

splinter

bar

above

it

(supporting

the

springs)

are

united

by

a

piece

of

wood

or

metal

called

a

futchel,

which

forms

a

socket

for

the

pole

that

extends

from

the

front

axle.

For

strength

and

support,

a

rod

called

the

backstay

may

extend

from

either

end

of

the

rear

axle

to

the

reach,

the

pole

or rod joining the hind axle to the forward bolster above the front axle.

A

skid

called

a

drag,

dragshoe,

shoe

or

skidpan

retards

the

motion

of

the

wheels.

A

London

patent

of

1841

describes

one

such

apparatus:

An

iron-shod

beam,

slightly

longer

than

the

radius

of

the

wheel,

is

hinged

under

the

axle

so

that

when

it

is

released

to

strike

the

ground

the

forward

momentum

of

the

vehicle

wedges

it

against

the

axle.

The

original

feature

of

this

modification

was

that,

instead

of

the

usual

practice

of

having

to

stop

the

carriage

to

retract

the

beam

and

so

lose

useful

momentum,

the

chain

holding

it

in

place

is

released

(from

the

driver's

position)

so

that

it

is

allowed

to

rotate

further

in

its

backwards

direction,

releasing

the

axle.

A

system of "pendant-levers" and straps then allows the beam to return to its first position and be ready for further use.[20]

A catch or block called a trigger may be used to hold a wheel on a declivity.

A

horizontal

wheel

or

segment

of

a

wheel

called

a

fifth

wheel

sometimes

forms

an

extended

support

to

prevent

the

carriage

from

tipping;

it

consists

of

two

parts

rotating

on

each

other

about

the

kingbolt

above

the

fore

axle

and

beneath

the

body.

A

block

of

wood

called a headblock might be placed between the fifth wheel and the forward spring.

Modern Chariot

Chinese Carriage

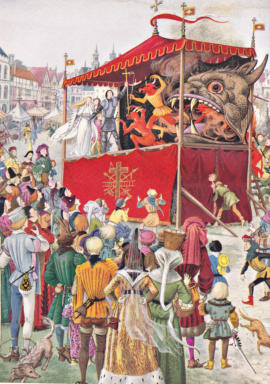

Pageant Wagon

Roman Carriage

Cobb & Co Coach

Governess’ Carriage

Hearse

Medieval Coach

Tipping Cart

Cart

The first camel in Australia.

The

Phillips

brothers,

(Henry

Weston

Phillips

(1818-

1898);

George

Phillips

(1820-1900);

G

M

Phillips

(?-

?))

bought

nine

camels

at

Tenerife

in

the

Canary

Islands.

Four

or

six

of

the

beasts

were

loaded

aboard

the

SS

Apolline

which

had

been

chartered

by

Henry

in

London.

The

Apolline,

under

Captain

William

Deane,

docked

at

Port

Adelaide

in

South

Australia

on

12

October

1840

and

the

sole

surviving

beast,

named

Harry, became the first camel in Australia.

By

the

mid–1800s,

exploration

in

Australia

was

at

its

peak

with

expeditions

setting

out

almost

monthly.

The

race

to

map

the

continent,

locate

natural

resources

or

find

new

places

to

settle

moved

away

from

the

coast

and

further

into

the

inhospitable

heart

of

Australia.

It

was

soon

obvious

that

the

traditional

horses

and

wagons

used

for

such

expeditions

were

not

suitable

in

this

strange

and

foreign

land.The

solution

to

the

problem

of

finding

suitable

transport

for

inland

exploration

and

travel

was

to

bring

in

camels.

As

nobody

at

the

time

knew

how

to

handle

camels,

cameleers

were

recruited

to

Australia

as

well.

The

introduction

of

camels

and

the

so-called

'Afghan'

cameleers

proved

to

be

a

turning

point

in

the

exploration and development of the Australian interior.

Afghan and Decorated Camel

Afghan

and

Decorated

Camel,

1901.

Image

courtesy

of the State Library of South Australia: B 14739.

For

a

short

period

of

time

from

the

1860s

to

the

early

1900s, these cameleers and their 'ships of the desert'

became

the

backbone

of

the

Australian

economy.

They

accompanied

exploration

parties,

carrying

supplies

and

materials

where

horses

and

oxen

could

not.

They

carted

supplies,

mail

and

even

water

to

remote

settlements.

They

transported

the

supplies,

tools

and

equipment

needed

for

the

surveying

and

construction

of

some

of

Australia's

earliest,

and

greatest,

infrastructure

projects,

such

as

the

Overland

Telegraph

and

Trans-

Australian Railway.

The first cameleers

In

the

1800s,

explorers,

settlers,

ranchers

and

prospectors

sought

to

unlock

the

mystery

and

potential

of

the

vast,

inhospitable

interior

of

Australia.

Horses,

and

to

a

lesser

degree

donkeys

and

bullocks,

were

the

traditional

beasts

of

burden

on

early

expeditions

into

Australia's

interior.

Many

of

these

expeditions

ended

in

disaster

and

tragedy.

As

well

as

requiring

regular

watering

and

large

stocks

of

feed,

horses

were

easily

exhausted

by

the

tough

and

often

sandy

ground

and

supposedly

'spooked'

by

the

Australian terrain.

One

camel

being

winched

over

the

side

of

the

boat

while a number of Afghans watch.

Unloading camels at Port Augusta, ca.1920.

Image

courtesy

of

the

State

Library

of

South

Australia: B 68916.

A 'solution to the problem'

As

early

as

1839,

camels

were

proposed

as

the

solution

to

the

problem

of

transport

while

exploring.

The

first

expedition

to

use

a

camel

was

the

1846

Horrocks

expedition.

'Harry',

as

the

camel

was

named

by

the

party,

proved

the

worth

of

using

camels

in

expeditions.

In

1846

a

Melbourne

newspaper

reported

that

the

camels

could

carry:

from

seven

to

eight

hundred

pounds

weight

...

they

last

out

several

generations

of

mules

...

the

price

paid

for

them

does

not

exceed

one

half

of

that

paid

for

mules

...

and

it

is

proved

that

these

'ships

of

the

deserts'

of

Arabia

are

equally adaptable to our climate.

Other

small

successes

followed

and

by

1858,

many

prominent

Australians

were

calling

for

the

introduction

of

camels,

including

South

Australian

Governor,

Richard MacDonnell:

“I

despair

of

much

being

achieved

even

with

horses;

and

I

certainly

think

we

have

never

given

explorers

fair

play

in

not

equipping

them

with

camels

or

dromedaries

and

waterskins,

which

in

Africa

I

found

the best methods of carrying liquid.”

Governor

Richard

MacDonnell

to

Charles

Sturt

10

August

1858.

Quoted

in

Mrs

Napier

Sturt's

'Life

of

Charles Sturt' (1899)

.

Purchase and recruitment

At

the

same

time,

the

Victorian

Expedition

Committee

commissioned

George

Landell,

a

well-known

horseman

who

exported

to

India,

to

buy

camels

and

recruit

cameleers,

because

'the

camels

would

be

comparatively

useless

unless

accompanied

by

their

native

drivers'

(from

VEE

committee

minutes,

19

May

1859).

The departure of the Burke and Wills expedition.

The

departure

of

the

Burke

and

Wills

expedition,

1881, Lithograph. Image courtesy of the

State Library of Victoria: mp010346.

In

1860,

24

camels

and

three

cameleers

from

arrived

in Melbourne to join the Burke and Wills

expedition.

Although

this

expedition

ended

in

disaster

with the loss of many lives, including those

of

Burke

and

Wills,

the

camels

again

proved

their

ability to survive the harsh and dry conditions of

the Australian outback.

By

the

late

1860s,

most

Australian

states

were

importing

camels

and

cameleers.

In

1866,

South

Australian

Samuel

Stuckey

brought

in

more

than

100

camels

and

31

cameleers.

Over

the

next

decade,

more

and

more

camels

and

cameleers

were

brought

to

Australia

as

breeding

programs

and

trading

routes

were

established.

It

is

estimated

that

from

1870

to

1900

alone,

more

than

2,000

cameleers

and

15,000

camels came to Australia.

Servicing infrastructure projects

The

cameleers

were

also

instrumental

in

the

success

of

some

of

early

Australia's

most

ambitious

infrastructure

projects.

They

carried

food

and

supplies

to

the

surveying

and

construction

teams

working

on

the

Overland

Telegraph,

which

ran

through

the

heart

of

the

continent

between

Adelaide

and

Darwin.

Once

the

project

was

completed,

they

continued

to

carry

supplies

and

mail

to

the

settlements

and

townships

which sprang up along the line.

They

also

operated

supply

and

equipment

trains

during

the

development

of

the

rail

link

between

Port

Augusta

and

Alice

Springs,

which

became

known

as

the

Afghan

Express,

and

later

the

Ghan.

The

Ghan's

emblem

is

an

Afghan

on

a

camel

in

recognition

of

their

efforts

in

opening

up

the

inhospitable

interior

to

the rest of Australia.

The cameleers

The Ghan Logo

The

Ghan

logo.

Image

courtesy

of

Great

Southern

Rail Limited.

The

cameleers

were

collectively

known

as

'Afghan'

cameleers.

While

some

were

originally

from

Afghanistan,

others

came

from

countries

such

as

Baluchistan,

Kashmir,

Sind,

Rajastan,

Egypt,

Persia,

Turkey

and

Punjab,

so

spoke

a

variety

of

languages.

Their

common

bond

was

their

Islamic

religion

and

the

fact

that

they

were

almost

exclusively

young

or

middle-aged men.

Not quite welcome

Almost

all

of

the

cameleers

who

came

to

Australia

during

this

period

faced

enormous

hardship.

While

their

skills

were

needed

and

mostly

appreciated,

they

were

largely

shunned

by

the

European

communities.

Indeed, racism and anger towards them was rife.

The Mosque, Marree

The

Mosque

at

Hergott

Springs.

The

pool

in

the

foreground

was

used

by

worshippers

for

washing

their feet before

entering

the

Mosque,

ca.1884.

Image

courtesy

of

the

State Library of South Australia: B 15341.

'Ghan Tours'

The

vast

majority

of

cameleers

arrived

in

Australia

alone,

leaving

wives

and

families

behind,

to

work

on

three

year

contracts.

They

were

either

given

living

quarters

on

a

breeding

station,

such

as

Thomas

Elder's

Beltana,

or

marginalised

on

the

outskirts

of

towns

and

settlements.

It

was

not

uncommon

for

outback

towns

to

have

three

distinct

areas—one

for

Europeans,

one

for

Aboriginals

and

one

for

cameleers,

which

became

known

as

Afghan,

or

Ghan,

towns.

This

social

division

was

even

reflected

in

the

town

cemeteries,

such

as

those

of

Farina

and

Marree.

But

while

it

was

extremely

rare

for

the

cameleers

to

interact

with

Europeans,

there

was

more

acceptance

by

the

local

Aboriginal

populations.

Indeed,

some

cameleers

married

local

Aboriginal

women

and

had

families here.

In

the

so-called

Ghan

towns,

cameleers

would

often

build

a

mosque

that

would

not

only

serve

as

a

place

of

worship,

but

as

a

gathering

place

that

offered

the

cameleers

a

sense

of

community

that

they

could

not

find

elsewhere.

The

remains

of

the

oldest

mosque

in

Australia,

built

in

1861,

are

near

Marree

(Hergott

Springs)

in

South

Australia.

This

was

once

one

of

the

country's

most

important

camel

junctions

and

in

its

heyday was called Little Asia or Little Afghanistan.

Portrait

of

Saidah

Saidel,

last

of

the

Afghan

camel

drivers

Robin

Smith,

Last

of

the

camel

drivers,

unknown.

Image courtesy of Territory Stories: PH0780/0010.

In

some

instances,

European

attitudes

to

the

cameleers

focused

on

their

religion.

In

other

cases,

it

was related to their

perceived

pride

and

independence

as

at

the

time,

Afghanistan

was

really

only

known

to

most

Australians as the country

that

had,

unlike

British

India,

resisted

the

British

forces.

This

perception

was

further

enhanced

in

the

settlers' eyes when

cameleers

on

Beltana

station

went

on

strike—one

of

Australia's first successful strikes.

Relations

on

the

Western

Australian

goldfields

1890s

As

the

cameleers

became

more

established,

many

set

up

their

own

competing

businesses

and

enterprises,

often

resulting

in

ill-will

and

sometimes

even

open

conflict.

One

of

the

most

notable

examples

of

this

was

on

the

Western

Australian

goldfields

in

the

late

1890s.

Years

of

simmering

tensions

between

Afghan

cameleers

and

European

bullock

teamsters

escalated

to

the

point

where

the

cameleers

were

openly

demonised

in

the

press

and

accused

of

various

acts

of

aggression,

including

monopolising

and

befouling

waterholes.

This

resulted

in

Hugh

Mahon,

the

local

federal

Member,

raising

the

issue

with Prime Minister Barton in parliament.

A

subsequent

investigation

by

police

was

ordered

and

the

state's

Police

Commissioner

ultimately

reported

that,

while

there

had

been

many

'reports

and

rumours

of

Afghans

polluting

the

water

and

taking

forcible

possession

of

dams',

there

was

actually

'no

evidence

obtainable'

to

support

these

reports

and

complaints.

In

fact,

the

investigation

found

that

the

only

trouble

'of

a

serious

nature'

was

that

a

cameleer

had

been

shot

and

wounded

by

a

white

teamster

for

failing

to

give

way.

Camel Train

Camel

train

laden

with

chaff

for

interior

stations

in

the

far

North

with

an

Afghan

camel

driver,

ca.1911.

Image

courtesy

of

the

State

Library

of

South

Australia:

B

14808.

Providing

drought

assistance

in

far

western

New

South Wales, 1900s

But

not

all

white

Australians

shunned

the

cameleers.

When William Goss became the first European to

see

Uluru,

he

named

a

nearby

well,

Kamran's

Well,

after his lead cameleer and a nearby hill, Allanah

Hill,

after

another

cameleer.

And

in

1902,

after

the

devastating Federation Drought, the Attorney-

General

received

a

letter

from

a

John

Edwards

stating that:

It

is

no

exaggeration

to

say

that

if

it

had

not

been

for

the

Afghan

and

his

Camels,

Wilcannia,

White

Cliffs,

Tibooburra,

Milperinka

and

other

Towns,

each

centres

of

considerable

population,

would

have

practically ceased to exist.

Contractors and entrepreneurs

As

the

cameleers

became

accustomed

to

the

Australian

landscape

and

people,

many

saw

a

way

to

create

opportunities

for

themselves

by

branching

into

business

on

their

own

or

in

partnership

with

Europeans.

So

successful

were

they

that

by

the

end

of

the

nineteenth

century,

Muslim

merchants

and

brokers dominated the Australian camel business.

Fuzzly Ahmed and Faiz Mahomet

Some

of

the

most

successful

of

the

cameleer

entrepreneurs

included

Fuzzly

Ahmed,

who

worked

the

Port

Augusta–Oodnadatta

line

for

many

years

before

moving

to

Broken

Hill,

and

Faiz

Mahomet,

who

arrived

at

the

age

of

22

and

settled

in

Marree,

where

he

operated

as

a

Forwarding

Agent

and

General

Carrier

before

moving

to

and

setting

up

an

operation

in

the

Coolgardie

goldfields

with

his

brother,

Tagh

Mahomet.

Abdul Wade

Camels

and

camel

merchants

at

Mt.

Garnet,

Queensland, ca. 1901

Unknown,

Camels

and

camel

merchants

at

Mt.

Garnet,

Queensland,

ca.

1901

[The

man

in

the

suit

and hat,

holding

the

camel,

is

Abdul

Wade].

Image

courtesy

of

the State Library of Queensland: 13127.

But

perhaps

the

most

successful

of

all

the

Afghan

cameleers

was

Abdul

Wade.

Wade

arrived

in

Australia in

1879

and

initially

worked

for

Faiz

and

Tagh

Mahomet.

In 1893, Wade moved to Bourke, NSW, and began

importing

camels

and

recruiting

Afghan

cameleers

for

the recently formed Bourke Camel Carrying Co.,

New South Wales.

In

1895,

Wade

married

widow

Emily

Ozadelle,

with

whom he had seven children, and in 1903 purchased

Wangamanna

station

in

New

South

Wales,

which

he

established

as

a

camel

breeding

and

carrying

business.

At

the

height

of

his

success,

Wade

had

four

hundred

camels and sixty men working for him.

Respected

by

his

employees

and

nicknamed

the

'Afghan

prince',

Wade

worked

hard

at

being

seen

as

an

equal

by

his

Australian

peers.

He

dressed

as

a

European,

educated

his

children

at

top

private

schools

and

even

became

a

naturalised

citizen.

But

success

in

Australian

society

eluded

Wade

and

his

attempts

at

fitting

in

were

ridiculed.

At

the

end

of

the

camel

era,

Wade

sold

his

station

and

returned

to

Afghanistan,

where

he

surrendered

his

Australian

passport.

The end of an era

In

the

early

twentieth

century,

motorised

and

rail

transport

was

becoming

more

common

and

the

need

for

camels,

and

cameleers,

was

slowly

dying.

Ironically,

two

of

the

greatest

contributions

of

the

Afghan

cameleers,

the

Ghan

railway

and

Overland

Telegraph,

were

also

to

herald

the

start

of

their

demise.

Immigration Restriction Act 1901

Certificate

exempting

Said

Kabool

from

the

Dictation

Test,

1916.

Said

Kabool

arrived

in

Australia

in

1896

and worked in

Coolgardie

for

seven

years.

Image

courtesy

of

the

National

Archives

of

Australia:

NAA:

E752,

1916/42,

p. 12.

As

many

of

the

cameleers

were

in

Australia

on

three

year

contracts,

they

would

usually

return

to

their

homes and family

after

each

contract,

before

returning

to

Australia.

Some

discovered

that

they

were

no

longer

granted

permission to return

to

Australia.

Others

found

that

they

now

had

to

sit

the

dictation

test

under

the

Immigration

Restriction

Act,

1901 (which

kept

out

new

cameleers

and

denied

re-entry

to

those

who

left),

or

apply

for

exemption.

Many

were

denied

naturalisation

due to their 'Asian' status.

In

1903,

a

petition

on

behalf

of

more

than

500

Indians

and

Afghans

in

Western

Australia

was

placed

before

the

Viceroy

of

India,

Lord

Curzon.

The

petition

made

four

major

complaints

against

'certain

legislative

restrictions'

facing

the

cameleers:

they

were

unable

to

hold

a

miner's

right

on

the

goldfields;

they

could

not

travel

interstate

for

work,

'except

under

the

most

stringent

conditions';

they

were

not

allowed

to

re-

enter

Australia

if

they

left;

and

they

were

not

able

to

be naturalised. Nothing was to come of their petition.

Rail and road transport

Feral

Camels

cover

approximately

40%

of

land

area

in the NT. Image courtesy of the Northern Territory

Government

Natural

Resources,

Environment,

The

Arts and Sport.

By

the

1930s,

Australia's

inland

transport

was

controlled

by

rail

and,

increasingly,

road

networks.

Facing

the

prospect

of

no

employment

and

a

sometimes

hostile

government

and

people,

many

of

the

cameleers

returned

to

their

homelands,

some

after

decades

of

living in Australia. Others remained and turned to

other

trades

and

means

of

making

a

living.

Rather

than see their camels shot, they released them into

the

wild,

where

they

have

since

flourished.

In

2007,

the estimated feral camel population of Australia

was

around

1

000

000,

approximately

half

of

which

were in Western Australia.

The last of the cameleers

By

1940,

few

cameleers

remained.

Philip

Jones

relates

the

tale

of

some

of

the

last

of

the

Afghan

cameleers

in

reCollections,

the

Journal

of

the

National Museum of Australia:

“In

the

Adelaide

summer

of

1952

a

young

Bosnian

Muslim

and

his

friends,

newly

arrived

immigrants,

pushed

open

the

high

gate

of

the

Adelaide

mosque

As

Shefik

Talanavic

entered

the

mosque

courtyard

he

was

confronted

by

an

extraordinary

sight.

Sitting

and

lying

on

benches,

shaded

from

the

strong

sunshine

by

vines

and

fruit

trees,

were

six

or

seven

ancient,

turbaned

men.

The

youngest

was

87

years

old.

Most

were

in

their

nineties;

the

oldest

was

117

years

old.

These

were

the

last

of

Australia's

Muslim

cameleers...

Several

had

subscribed

money

during

the

late

1880s

for

the

construction

of

the

mosque

which

now,

crumbling and decayed, provided their last refuge.”

It

is

only

in

recent

years,

with

the

South

Australian

Museum's

Australian

Muslim

Cameleers

exhibition

(developed

with

support

from

the

Visions

of

Australia

program)

and

book,

that

the

story

and

the

contribution

of

these

pioneers

to

Australia's

history

and

development has been told.

Australia’s Muslim Cameleers exhibition pictures &

dialogue courtesy ABC Alice Springs.

…. CLICK TO VIEW

The above information and more can be accessed on the

Australian Government website

http://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story

/afghan-cameleers