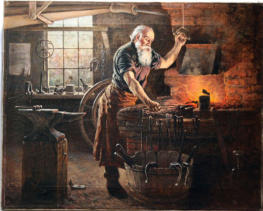

The Black Smith or Smithy

A

blacksmith

is

a

metalsmith

who

creates

objects

from

wrought

iron

or

steel

by

forging

the

metal,

using

tools

to

hammer,

bend,

and

cut

(cf.

whitesmith).

Blacksmiths

produce

objects

such

as

gates,

grilles,

railings,

light

fixtures,

furniture,

sculpture,

tools,

agricultural

implements, decorative and religious items, cooking utensils and weapons.

While

there

are

many

people

who

work

with

metal

such

as

farriers,

wheelwrights,

and

armorers,

the

blacksmith

had

a

general

knowledge

of

how

to

make

and

repair

many

things,

from

the

most

complex

of

weapons

and

armor

to

simple

things

like

nails

or

lengths of chain.

Origin of the term

The

"black"

in

"blacksmith"

refers

to

the

black

fire

scale,

a

layer

of

oxides

that

forms

on

the

surface

of

the

metal

during

heating.

The

origin

of

"smith"

is

debated,

it

may

come

from

the

old

English

word

"smythe"

meaning

"to

strike"

or

it

may

have

originated

from

the

Proto-German "smithaz" meaning "skilled worker."

Blacksmiths

work

by

heating

pieces

of

wrought

iron

or

steel

until

the

metal

becomes

soft

enough

for

shaping

with

hand

tools,

such

as

a hammer, anvil and chisel. Heating generally takes place in a forge fueled by propane, natural gas, coal, charcoal, coke or oil.

Some

modern

blacksmiths

may

also

employ

an

oxyacetylene

or

similar

blowtorch

for

more

localized

heating.

Induction

heating

methods are gaining popularity among modern blacksmiths.

Color

is

important

for

indicating

the

temperature

and

workability

of

the

metal.

As

iron

heats

to

higher

temperatures,

it

first

glows

red,

then

orange,

yellow,

and

finally

white.

The

ideal

heat

for

most

forging

is

the

bright

yellow-orange

color

that

indicates

forging

heat.

Because

they

must

be

able

to

see

the

glowing

color

of

the

metal,

some

blacksmiths

work

in

dim,

low-light

conditions,

but

most

work

in

well-lit conditions. The key is to have consistent lighting, but not too bright. Direct sunlight obscures the colors.

The techniques of smithing can be roughly divided into forging (sometimes called "sculpting"), welding, heat-treating, and finishing.

Forging

Forging—the

process

smiths

use

to

shape

metal

by

hammering—differs

from

machining

in

that

forging

does

not

remove

material.

Instead,

the

smith

hammers

the

iron

into

shape.

Even

punching

and

cutting

operations

(except

when

trimming

waste)

by

smiths

usually re-arrange metal around the hole, rather than drilling it out as swarf.

Forging uses seven basic operations or techniques:

Drawing down

Shrinking (a type of upsetting)

Bending

Upsetting

Swaging

Punching

Forge welding

These

operations

generally

require

at

least

a

hammer

and

anvil,

but

smiths

also

use

other

tools

and

techniques

to

accommodate

odd-sized or repetitive jobs.

Drawing

Drawing

lengthens

the

metal

by

reducing

one

or

both

of

the

other

two

dimensions.

As

the

depth

is

reduced,

or

the

width

narrowed,

the piece is lengthened or "drawn out."

As

an

example

of

drawing,

a

smith

making

a

chisel

might

flatten

a

square

bar

of

steel,

lengthening

the

metal,

reducing

its

depth

but

keeping its width consistent.

Drawing

does

not

have

to

be

uniform.

A

taper

can

result

as

in

making

a

wedge

or

a

woodworking

chisel

blade.

If

tapered

in

two

dimensions, a point results.

Drawing

can

be

accomplished

with

a

variety

of

tools

and

methods.

Two

typical

methods

using

only

hammer

and

anvil

would

be

hammering on the anvil horn, and hammering on the anvil face using the cross peen of a hammer.

Another

method

for

drawing

is

to

use

a

tool

called

a

fuller,

or

the

peen

of

the

hammer,

to

hasten

the

drawing

out

of

a

thick

piece

of

metal.

(The

technique

is

called

fullering

from

the

tool.)

Fullering

consists

of

hammering

a

series

of

indentations

with

corresponding

ridges,

perpendicular

to

the

long

section

of

the

piece

being

drawn.

The

resulting

effect

looks

somewhat

like

waves

along

the

top

of

the

piece.

Then

the

smith

turns

the

hammer

over

to

use

the

flat

face

to

hammer

the

tops

of

the

ridges

down

level

with

the

bottoms

of

the

indentations.

This

forces

the

metal

to

grow

in

length

(and

width

if

left

unchecked)

much

faster

than

just

hammering

with

the

flat

face of the hammer.

Bending

Heating iron to a "forging heat" allows bending as if it were a soft, ductile metal, like copper or silver.

Bending

can

be

done

with

the

hammer

over

the

horn

or

edge

of

the

anvil

or

by

inserting

a

bending

fork

into

the

Hardy

Hole

(the

square

hole

in

the

top

of

the

anvil),

placing

the

work

piece

between

the

tines

of

the

fork,

and

bending

the

material

to

the

desired

angle. Bends can be dressed and tightened, or widened, by hammering them over the appropriately shaped part of the anvil.

Some

metals

are

"hot

short",

meaning

they

lose

their

tensile

strength

when

heated.

They

become

like

Plasticine:

although

they

may

still

be

manipulated

by

squeezing,

an

attempt

to

stretch

them,

even

by

bending

or

twisting,

is

likely

to

have

them

crack

and

break

apart.

This

is

a

problem

for

some

blade-making

steels,

which

must

be

worked

carefully

to

avoid

developing

hidden

cracks

that

would

cause

failure

in

the

future.

Though

rarely

hand-worked,

titanium

is

notably

hot

short.

Even

such

common

smithing

processes

as

decoratively twisting a bar are impossible with it.

Upsetting

Upsetting

is

the

process

of

making

metal

thicker

in

one

dimension

through

shortening

in

the

other.

One

form

is

to

heat

the

end

of

a

rod

and

then

hammer

on

it

as

one

would

drive

a

nail:

the

rod

gets

shorter,

and

the

hot

part

widens.

An

alternative

to

hammering

on

the hot end is to place the hot end on the anvil and hammer on the cold end.

Punching

Punching

may

be

done

to

create

a

decorative

pattern,

or

to

make

a

hole.

For

example,

in

preparation

for

making

a

hammerhead,

a

smith

would

punch

a

hole

in

a

heavy

bar

or

rod

for

the

hammer

handle.

Punching

is

not

limited

to

depressions

and

holes.

It

also

includes cutting, slitting, and drifting—all done with a chisel.

Combining processes

The

five

basic

forging

processes

are

often

combined

to

produce

and

refine

the

shapes

necessary

for

finished

products.

For

example,

to

fashion

a

cross-peen

hammer

head,

a

smith

would

start

with

a

bar

roughly

the

diameter

of

the

hammer

face:

the

handle

hole

would

be

punched

and

drifted

(widened

by

inserting

or

passing

a

larger

tool

through

it),

the

head

would

be

cut

(punched,

but

with

a

wedge),

the peen would be drawn to a wedge, and the face would be dressed by upsetting.

As

with

making

a

chisel,

since

it

is

lengthened

by

drawing

it

would

also

tend

to

spread

in

width.

A

smith

would

therefore

frequently

turn the chisel-to-be on its side and hammer it back down—upsetting it—to check the spread and keep the metal at the correct width.

Or,

if

a

smith

needed

to

put

a

90-degree

bend

in

a

bar

and

wanted

a

sharp

corner

on

the

outside

of

the

bend,

they

would

begin

by

hammering

an

unsupported

end

to

make

the

curved

bend.

Then,

to

"fatten

up"

the

outside

radius

of

the

bend,

one

or

both

arms

of

the

bend

would

need

to

be

pushed

back

to

fill

the

outer

radius

of

the

curve.

So

they

would

hammer

the

ends

of

the

stock

down

into

the

bend,

'upsetting'

it

at

the

point

of

the

bend.

They

would

then

dress

the

bend

by

drawing

the

sides

of

the

bend

to

keep

the

correct

thickness.

The

hammering

would

continue—upsetting

and

then

drawing—until

the

curve

had

been

properly

shaped.

In

the

primary

operation was the bend, but the drawing and upsetting are done to refine the shape.

Welding

Welding is the joining of the same or similar kind of metal.

A

modern

blacksmith

has

a

range

of

options

and

tools

to

accomplish

this.

The

basic

types

of

welding

commonly

employed

in

a

modern workshop include traditional forge welding as well as modern methods, including oxyacetylene and arc welding.

In

forge

welding,

the

pieces

to

join

are

heated

to

what

is

generally

referred

to

as

welding

heat.

For

mild

steel

most

smiths

judge

this

temperature by color: the metal glows an intense yellow or white. At this temperature the steel is near molten.

Any

foreign

material

in

the

weld,

such

as

the

oxides

or

"scale"

that

typically

form

in

the

fire,

can

weaken

it

and

cause

it

to

fail.

Thus

the

mating

surfaces

to

be

joined

must

be

kept

clean.

To

this

end

a

smith

makes

sure

the

fire

is

a

reducing

fire:

a

fire

where,

at

the

heart,

there

is

a

great

deal

of

heat

and

very

little

oxygen.

The

smith

also

carefully

shapes

mating

faces

so

that

as

they

come

together

foreign

material

squeezes

out

as

the

metal

is

joined.

To

clean

the

faces,

protect

them

from

oxidation,

and

provide

a

medium

to

carry

foreign material out of the weld, the smith sometimes uses flux—typically powdered borax, silica sand, or both.

The

smith

first

cleans

parts

to

be

joined

with

a

wire

brush,

then

puts

them

in

the

fire

to

heat.

With

a

mix

of

drawing

and

upsetting

the

smith

shapes

the

faces

so

that

when

finally

brought

together,

the

center

of

the

weld

connects

first

and

the

connection

spreads

outward under the hammer blows, pushing out the flux (if used) and foreign material.

The

dressed

metal

goes

back

in

the

fire,

is

brought

near

to

welding

heat,

removed

from

the

fire,

and

brushed.

Flux

is

sometimes

applied,

which

prevents

oxygen

from

reaching

and

burning

the

metal

during

forging,

and

it

is

returned

to

the

fire.

The

smith

now

watches

carefully

to

avoid

overheating

the

metal.

There

is

some

challenge

to

this

because,

to

see

the

color

of

the

metal,

the

smith

must

remove

it

from

the

fire—exposing

it

to

air,

which

can

rapidly

oxidize

it.

So

the

smith

might

probe

into

the

fire

with

a

bit

of

steel

wire,

prodding

lightly

at

the

mating

faces.

When

the

end

of

the

wire

sticks

on

to

the

metal,

it

is

at

the

right

temperature

(a

small

weld

forms

where

the

wire

touches

the

mating

face,

so

it

sticks).

The

smith

commonly

places

the

metal

in

the

fire

so

he

can

see

it

without

letting

surrounding

air

contact

the

surface.

(Note

that

smiths

don't

always

use

flux,

especially

in

the

UK.)

Now

the

smith

moves

with

rapid

purpose,

quickly

taking

the

metal

from

the

fire

to

the

anvil

and

bringing

the

mating

faces

together.

A

few

light

hammer

taps

bring

the

mating

faces

into

complete

contact

and

squeeze

out

the

flux—and

finally,

the

smith

returns

the

work

to

the

fire.

The

weld

begins

with

the

taps,

but

often

the

joint

is

weak

and

incomplete,

so

the

smith

reheats

the

joint

to

welding

temperature

and

works

the

weld

with light blows to "set" the weld and finally to dress it to the shape.

Finishing

Depending on the intended use of the piece, a blacksmith may finish it in a number of ways:

A

simple

jig

(a

tool)

that

the

smith

might

only

use

a

few

times

in

the

shop

may

get

the

minimum

of

finishing—a

rap

on

the

anvil

to

break off scale and a brushing with a wire brush.

Files bring a piece to final shape, removing burrs and sharp edges, and smoothing the surface.

Heat treatment and case-hardening achieve the desired hardness.

The wire brush—as a hand tool or power tool—can further smooth, brighten, and polish surfaces.

Grinding stones, abrasive paper, and emery wheels can further shape, smooth, and polish the surface.

A

range

of

treatments

and

finishes

can

inhibit

oxidation

and

enhance

or

change

the

appearance

of

the

piece.

An

experienced

smith

selects

the

finish

based

on

the

metal

and

on

the

intended

use

of

the

item.

Finishes

include

(among

others):

paint,

varnish,

bluing,

browning, oil, and wax.

Striker

Blacksmith's striker

A

blacksmith's

striker

is

an

assistant

(frequently

an

apprentice),

whose

job

it

is

to

swing

a

large

sledgehammer

in

heavy

forging

operations,

as

directed

by

the

blacksmith.

In

practice,

the

blacksmith

holds

the

hot

iron

at

the

anvil

(with

tongs)

in

one

hand,

and

indicates

where

to

strike

the

iron

by

tapping

it

with

a

small

hammer

in

the

other

hand.

The

striker

then

delivers

a

heavy

blow

to

the

indicated

spot

with

a

sledgehammer.

During

the

20th

century

and

into

the

21st

century,

this

role

has

become

increasingly

unnecessary and automated through the use of trip hammers or reciprocating power hammers.

The blacksmith's materials

When

iron

ore

is

smelted

into

usable

metal,

a

certain

amount

of

carbon

is

usually

alloyed

with

the

iron.

(Charcoal

is

almost

pure

carbon.)

The

amount

of

carbon

significantly

affects

the

properties

of

the

metal.

If

the

carbon

content

is

over

2%,

the

metal

is

called

cast

iron,

because

it

has

a

relatively

low

melting

point

and

is

easily

cast.

It

is

quite

brittle,

however,

and

cannot

be

forged

so

therefore

not

used

for

blacksmithing.

If

the

carbon

content

is

between

0.25%

and

2%,

the

resulting

metal

is

tool

grade

steel,

which

can

be

heat

treated

as

discussed

above.

When

the

carbon

content

is

below

0.25%,

the

metal

is

either

"wrought

iron

(wrought

iron

is

not

smelted

and

cannot

come

from

this

process)

"

or

"mild

steel."

The

terms

are

never

interchangeable.

In

preindustrial

times,

the

material

of

choice

for

blacksmiths

was

wrought

iron.

This

iron

had

a

very

low

carbon

content,

and

also

included

up

to

5%

of

glassy

iron

silicate

slag

in

the

form

of

numerous

very

fine

stringers.

This

slag

content

made

the

iron

very

tough,

gave

it

considerable

resistance

to

rusting,

and

allowed

it

to

be

more

easily

"forge

welded,"

a

process

in

which

the

blacksmith

permanently

joins

two

pieces

of

iron,

or

a

piece

of

iron

and

a

piece

of

steel,

by

heating

them

nearly

to

a

white

heat

and

hammering

them

together.

Forge

welding

is

more

difficult

with

modern

mild

steel,

because

it

welds

in

a

narrower

temperature

band.

The

fibrous

nature

of

wrought

iron

required

knowledge

and

skill

to

properly

form

any

tool

which

would

be

subject

to

stress.

Modern

steel

is

produced

using

either

the

blast

furnace

or

arc

furnaces.

Wrought

iron

was

produced

by

a

labor-intensive

process

called

puddling,

so

this

material

is

now

a

difficult-to-

find

specialty

product.

Modern

blacksmiths

generally

substitute

mild

steel

for

making

objects

traditionally

of

wrought

iron.

Sometimes

they use electrolytic-process pure iron.

Many

blacksmiths

also

incorporate

materials

such

as

bronze,

copper,

or

brass

in

artistic

products.

Aluminum

and

titanium

may

also

be

forged

by

the

blacksmith's

process.

Each

material

responds

differently

under

the

hammer

and

must

be

separately

studied

by

the

blacksmith.

Workmen in the sunshine harvester factory … picture courtesy the

Museums Of Victoria

The first camel in Australia.

The

Phillips

brothers,

(Henry

Weston

Phillips

(1818-

1898);

George

Phillips

(1820-1900);

G

M

Phillips

(?-

?))

bought

nine

camels

at

Tenerife

in

the

Canary

Islands.

Four

or

six

of

the

beasts

were

loaded

aboard

the

SS

Apolline

which

had

been

chartered

by

Henry

in

London.

The

Apolline,

under

Captain

William

Deane,

docked

at

Port

Adelaide

in

South

Australia

on

12

October

1840

and

the

sole

surviving

beast,

named

Harry, became the first camel in Australia.

By

the

mid–1800s,

exploration

in

Australia

was

at

its

peak

with

expeditions

setting

out

almost

monthly.

The

race

to

map

the

continent,

locate

natural

resources

or

find

new

places

to

settle

moved

away

from

the

coast

and

further

into

the

inhospitable

heart

of

Australia.

It

was

soon

obvious

that

the

traditional

horses

and

wagons

used

for

such

expeditions

were

not

suitable

in

this

strange

and

foreign

land.The

solution

to

the

problem

of

finding

suitable

transport

for

inland

exploration

and

travel

was

to

bring

in

camels.

As

nobody

at

the

time

knew

how

to

handle

camels,

cameleers

were

recruited

to

Australia

as

well.

The

introduction

of

camels

and

the

so-called

'Afghan'

cameleers

proved

to

be

a

turning

point

in

the

exploration and development of the Australian interior.

Afghan and Decorated Camel

Afghan

and

Decorated

Camel,

1901.

Image

courtesy

of the State Library of South Australia: B 14739.

For

a

short

period

of

time

from

the

1860s

to

the

early

1900s, these cameleers and their 'ships of the desert'

became

the

backbone

of

the

Australian

economy.

They

accompanied

exploration

parties,

carrying

supplies

and

materials

where

horses

and

oxen

could

not.

They

carted

supplies,

mail

and

even

water

to

remote

settlements.

They

transported

the

supplies,

tools

and

equipment

needed

for

the

surveying

and

construction

of

some

of

Australia's

earliest,

and

greatest,

infrastructure

projects,

such

as

the

Overland

Telegraph

and

Trans-

Australian Railway.

The first cameleers

In

the

1800s,

explorers,

settlers,

ranchers

and

prospectors

sought

to

unlock

the

mystery

and

potential

of

the

vast,

inhospitable

interior

of

Australia.

Horses,

and

to

a

lesser

degree

donkeys

and

bullocks,

were

the

traditional

beasts

of

burden

on

early

expeditions

into

Australia's

interior.

Many

of

these

expeditions

ended

in

disaster

and

tragedy.

As

well

as

requiring

regular

watering

and

large

stocks

of

feed,

horses

were

easily

exhausted

by

the

tough

and

often

sandy

ground

and

supposedly

'spooked'

by

the

Australian terrain.

One

camel

being

winched

over

the

side

of

the

boat

while a number of Afghans watch.

Unloading camels at Port Augusta, ca.1920.

Image

courtesy

of

the

State

Library

of

South

Australia: B 68916.

A 'solution to the problem'

As

early

as

1839,

camels

were

proposed

as

the

solution

to

the

problem

of

transport

while

exploring.

The

first

expedition

to

use

a

camel

was

the

1846

Horrocks

expedition.

'Harry',

as

the

camel

was

named

by

the

party,

proved

the

worth

of

using

camels

in

expeditions.

In

1846

a

Melbourne

newspaper

reported

that

the

camels

could

carry:

from

seven

to

eight

hundred

pounds

weight

...

they

last

out

several

generations

of

mules

...

the

price

paid

for

them

does

not

exceed

one

half

of

that

paid

for

mules

...

and

it

is

proved

that

these

'ships

of

the

deserts'

of

Arabia

are

equally adaptable to our climate.

Other

small

successes

followed

and

by

1858,

many

prominent

Australians

were

calling

for

the

introduction

of

camels,

including

South

Australian

Governor,

Richard MacDonnell:

“I

despair

of

much

being

achieved

even

with

horses;

and

I

certainly

think

we

have

never

given

explorers

fair

play

in

not

equipping

them

with

camels

or

dromedaries

and

waterskins,

which

in

Africa

I

found

the best methods of carrying liquid.”

Governor

Richard

MacDonnell

to

Charles

Sturt

10

August

1858.

Quoted

in

Mrs

Napier

Sturt's

'Life

of

Charles Sturt' (1899)

.

Purchase and recruitment

At

the

same

time,

the

Victorian

Expedition

Committee

commissioned

George

Landell,

a

well-known

horseman

who

exported

to

India,

to

buy

camels

and

recruit

cameleers,

because

'the

camels

would

be

comparatively

useless

unless

accompanied

by

their

native

drivers'

(from

VEE

committee

minutes,

19

May

1859).

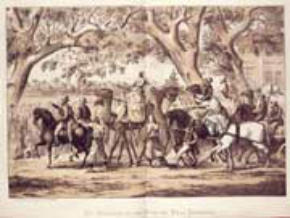

The departure of the Burke and Wills expedition.

The

departure

of

the

Burke

and

Wills

expedition,

1881, Lithograph. Image courtesy of the

State Library of Victoria: mp010346.

In

1860,

24

camels

and

three

cameleers

from

arrived

in Melbourne to join the Burke and Wills

expedition.

Although

this

expedition

ended

in

disaster

with the loss of many lives, including those

of

Burke

and

Wills,

the

camels

again

proved

their

ability to survive the harsh and dry conditions of

the Australian outback.

By

the

late

1860s,

most

Australian

states

were

importing

camels

and

cameleers.

In

1866,

South

Australian

Samuel

Stuckey

brought

in

more

than

100

camels

and

31

cameleers.

Over

the

next

decade,

more

and

more

camels

and

cameleers

were

brought

to

Australia

as

breeding

programs

and

trading

routes

were

established.

It

is

estimated

that

from

1870

to

1900

alone,

more

than

2,000

cameleers

and

15,000

camels came to Australia.

Servicing infrastructure projects

The

cameleers

were

also

instrumental

in

the

success

of

some

of

early

Australia's

most

ambitious

infrastructure

projects.

They

carried

food

and

supplies

to

the

surveying

and

construction

teams

working

on

the

Overland

Telegraph,

which

ran

through

the

heart

of

the

continent

between

Adelaide

and

Darwin.

Once

the

project

was

completed,

they

continued

to

carry

supplies

and

mail

to

the

settlements

and

townships

which sprang up along the line.

They

also

operated

supply

and

equipment

trains

during

the

development

of

the

rail

link

between

Port

Augusta

and

Alice

Springs,

which

became

known

as

the

Afghan

Express,

and

later

the

Ghan.

The

Ghan's

emblem

is

an

Afghan

on

a

camel

in

recognition

of

their

efforts

in

opening

up

the

inhospitable

interior

to

the rest of Australia.

The cameleers

The Ghan Logo

The

Ghan

logo.

Image

courtesy

of

Great

Southern

Rail Limited.

The

cameleers

were

collectively

known

as

'Afghan'

cameleers.

While

some

were

originally

from

Afghanistan,

others

came

from

countries

such

as

Baluchistan,

Kashmir,

Sind,

Rajastan,

Egypt,

Persia,

Turkey

and

Punjab,

so

spoke

a

variety

of

languages.

Their

common

bond

was

their

Islamic

religion

and

the

fact

that

they

were

almost

exclusively

young

or

middle-aged men.

Not quite welcome

Almost

all

of

the

cameleers

who

came

to

Australia

during

this

period

faced

enormous

hardship.

While

their

skills

were

needed

and

mostly

appreciated,

they

were

largely

shunned

by

the

European

communities.

Indeed, racism and anger towards them was rife.

The Mosque, Marree

The

Mosque

at

Hergott

Springs.

The

pool

in

the

foreground

was

used

by

worshippers

for

washing

their feet before

entering

the

Mosque,

ca.1884.

Image

courtesy

of

the

State Library of South Australia: B 15341.

'Ghan Tours'

The

vast

majority

of

cameleers

arrived

in

Australia

alone,

leaving

wives

and

families

behind,

to

work

on

three

year

contracts.

They

were

either

given

living

quarters

on

a

breeding

station,

such

as

Thomas

Elder's

Beltana,

or

marginalised

on

the

outskirts

of

towns

and

settlements.

It

was

not

uncommon

for

outback

towns

to

have

three

distinct

areas—one

for

Europeans,

one

for

Aboriginals

and

one

for

cameleers,

which

became

known

as

Afghan,

or

Ghan,

towns.

This

social

division

was

even

reflected

in

the

town

cemeteries,

such

as

those

of

Farina

and

Marree.

But

while

it

was

extremely

rare

for

the

cameleers

to

interact

with

Europeans,

there

was

more

acceptance

by

the

local

Aboriginal

populations.

Indeed,

some

cameleers

married

local

Aboriginal

women

and

had

families here.

In

the

so-called

Ghan

towns,

cameleers

would

often

build

a

mosque

that

would

not

only

serve

as

a

place

of

worship,

but

as

a

gathering

place

that

offered

the

cameleers

a

sense

of

community

that

they

could

not

find

elsewhere.

The

remains

of

the

oldest

mosque

in

Australia,

built

in

1861,

are

near

Marree

(Hergott

Springs)

in

South

Australia.

This

was

once

one

of

the

country's

most

important

camel

junctions

and

in

its

heyday was called Little Asia or Little Afghanistan.

Portrait

of

Saidah

Saidel,

last

of

the

Afghan

camel

drivers

Robin

Smith,

Last

of

the

camel

drivers,

unknown.

Image courtesy of Territory Stories: PH0780/0010.

In

some

instances,

European

attitudes

to

the

cameleers

focused

on

their

religion.

In

other

cases,

it

was related to their

perceived

pride

and

independence

as

at

the

time,

Afghanistan

was

really

only

known

to

most

Australians as the country

that

had,

unlike

British

India,

resisted

the

British

forces.

This

perception

was

further

enhanced

in

the

settlers' eyes when

cameleers

on

Beltana

station

went

on

strike—one

of

Australia's first successful strikes.

Relations

on

the

Western

Australian

goldfields

1890s

As

the

cameleers

became

more

established,

many

set

up

their

own

competing

businesses

and

enterprises,

often

resulting

in

ill-will

and

sometimes

even

open

conflict.

One

of

the

most

notable

examples

of

this

was

on

the

Western

Australian

goldfields

in

the

late

1890s.

Years

of

simmering

tensions

between

Afghan

cameleers

and

European

bullock

teamsters

escalated

to

the

point

where

the

cameleers

were

openly

demonised

in

the

press

and

accused

of

various

acts

of

aggression,

including

monopolising

and

befouling

waterholes.

This

resulted

in

Hugh

Mahon,

the

local

federal

Member,

raising

the

issue

with Prime Minister Barton in parliament.

A

subsequent

investigation

by

police

was

ordered

and

the

state's

Police

Commissioner

ultimately

reported

that,

while

there

had

been

many

'reports

and

rumours

of

Afghans

polluting

the

water

and

taking

forcible

possession

of

dams',

there

was

actually

'no

evidence

obtainable'

to

support

these

reports

and

complaints.

In

fact,

the

investigation

found

that

the

only

trouble

'of

a

serious

nature'

was

that

a

cameleer

had

been

shot

and

wounded

by

a

white

teamster

for

failing

to

give

way.

Camel Train

Camel

train

laden

with

chaff

for

interior

stations

in

the

far

North

with

an

Afghan

camel

driver,

ca.1911.

Image

courtesy

of

the

State

Library

of

South

Australia:

B

14808.

Providing

drought

assistance

in

far

western

New

South Wales, 1900s

But

not

all

white

Australians

shunned

the

cameleers.

When William Goss became the first European to

see

Uluru,

he

named

a

nearby

well,

Kamran's

Well,

after his lead cameleer and a nearby hill, Allanah

Hill,

after

another

cameleer.

And

in

1902,

after

the

devastating Federation Drought, the Attorney-

General

received

a

letter

from

a

John

Edwards

stating that:

It

is

no

exaggeration

to

say

that

if

it

had

not

been

for

the

Afghan

and

his

Camels,

Wilcannia,

White

Cliffs,

Tibooburra,

Milperinka

and

other

Towns,

each

centres

of

considerable

population,

would

have

practically ceased to exist.

Contractors and entrepreneurs

As

the

cameleers

became

accustomed

to

the

Australian

landscape

and

people,

many

saw

a

way

to

create

opportunities

for

themselves

by

branching

into

business

on

their

own

or

in

partnership

with

Europeans.

So

successful

were

they

that

by

the

end

of

the

nineteenth

century,

Muslim

merchants

and

brokers dominated the Australian camel business.

Fuzzly Ahmed and Faiz Mahomet

Some

of

the

most

successful

of

the

cameleer

entrepreneurs

included

Fuzzly

Ahmed,

who

worked

the

Port

Augusta–Oodnadatta

line

for

many

years

before

moving

to

Broken

Hill,

and

Faiz

Mahomet,

who

arrived

at

the

age

of

22

and

settled

in

Marree,

where

he

operated

as

a

Forwarding

Agent

and

General

Carrier

before

moving

to

and

setting

up

an

operation

in

the

Coolgardie

goldfields

with

his

brother,

Tagh

Mahomet.

Abdul Wade

Camels

and

camel

merchants

at

Mt.

Garnet,

Queensland, ca. 1901

Unknown,

Camels

and

camel

merchants

at

Mt.

Garnet,

Queensland,

ca.

1901

[The

man

in

the

suit

and hat,

holding

the

camel,

is

Abdul

Wade].

Image

courtesy

of

the State Library of Queensland: 13127.

But

perhaps

the

most

successful

of

all

the

Afghan

cameleers

was

Abdul

Wade.

Wade

arrived

in

Australia in

1879

and

initially

worked

for

Faiz

and

Tagh

Mahomet.

In 1893, Wade moved to Bourke, NSW, and began

importing

camels

and

recruiting

Afghan

cameleers

for

the recently formed Bourke Camel Carrying Co.,

New South Wales.

In

1895,

Wade

married

widow

Emily

Ozadelle,

with

whom he had seven children, and in 1903 purchased

Wangamanna

station

in

New

South

Wales,

which

he

established

as

a

camel

breeding

and

carrying

business.

At

the

height

of

his

success,

Wade

had

four

hundred

camels and sixty men working for him.

Respected

by

his

employees

and

nicknamed

the

'Afghan

prince',

Wade

worked

hard

at

being

seen

as

an

equal

by

his

Australian

peers.

He

dressed

as

a

European,

educated

his

children

at

top

private

schools

and

even

became

a

naturalised

citizen.

But

success

in

Australian

society

eluded

Wade

and

his

attempts

at

fitting

in

were

ridiculed.

At

the

end

of

the

camel

era,

Wade

sold

his

station

and

returned

to

Afghanistan,

where

he

surrendered

his

Australian

passport.

The end of an era

In

the

early

twentieth

century,

motorised

and

rail

transport

was

becoming

more

common

and

the

need

for

camels,

and

cameleers,

was

slowly

dying.

Ironically,

two

of

the

greatest

contributions

of

the

Afghan

cameleers,

the

Ghan

railway

and

Overland

Telegraph,

were

also

to

herald

the

start

of

their

demise.

Immigration Restriction Act 1901

Certificate

exempting

Said

Kabool

from

the

Dictation

Test,

1916.

Said

Kabool

arrived

in

Australia

in

1896

and worked in

Coolgardie

for

seven

years.

Image

courtesy

of

the

National

Archives

of

Australia:

NAA:

E752,

1916/42,

p. 12.

As

many

of

the

cameleers

were

in

Australia

on

three

year

contracts,

they

would

usually

return

to

their

homes and family

after

each

contract,

before

returning

to

Australia.

Some

discovered

that

they

were

no

longer

granted

permission to return

to

Australia.

Others

found

that

they

now

had

to

sit

the

dictation

test

under

the

Immigration

Restriction

Act,

1901 (which

kept

out

new

cameleers

and

denied

re-entry

to

those

who

left),

or

apply

for

exemption.

Many

were

denied

naturalisation

due to their 'Asian' status.

In

1903,

a

petition

on

behalf

of

more

than

500

Indians

and

Afghans

in

Western

Australia

was

placed

before

the

Viceroy

of

India,

Lord

Curzon.

The

petition

made

four

major

complaints

against

'certain

legislative

restrictions'

facing

the

cameleers:

they

were

unable

to

hold

a

miner's

right

on

the

goldfields;

they

could

not

travel

interstate

for

work,

'except

under

the

most

stringent

conditions';

they

were

not

allowed

to

re-

enter

Australia

if

they

left;

and

they

were

not

able

to

be naturalised. Nothing was to come of their petition.

Rail and road transport

Feral

Camels

cover

approximately

40%

of

land

area

in the NT. Image courtesy of the Northern Territory

Government

Natural

Resources,

Environment,

The

Arts and Sport.

By

the

1930s,

Australia's

inland

transport

was

controlled

by

rail

and,

increasingly,

road

networks.

Facing

the

prospect

of

no

employment

and

a

sometimes

hostile

government

and

people,

many

of

the

cameleers

returned

to

their

homelands,

some

after

decades

of

living in Australia. Others remained and turned to

other

trades

and

means

of

making

a

living.

Rather

than see their camels shot, they released them into

the

wild,

where

they

have

since

flourished.

In

2007,

the estimated feral camel population of Australia

was

around

1

000

000,

approximately

half

of

which

were in Western Australia.

The last of the cameleers

By

1940,

few

cameleers

remained.

Philip

Jones

relates

the

tale

of

some

of

the

last

of

the

Afghan

cameleers

in

reCollections,

the

Journal

of

the

National Museum of Australia:

“In

the

Adelaide

summer

of

1952

a

young

Bosnian

Muslim

and

his

friends,

newly

arrived

immigrants,

pushed

open

the

high

gate

of

the

Adelaide

mosque

As

Shefik

Talanavic

entered

the

mosque

courtyard

he

was

confronted

by

an

extraordinary

sight.

Sitting

and

lying

on

benches,

shaded

from

the

strong

sunshine

by

vines

and

fruit

trees,

were

six

or

seven

ancient,

turbaned

men.

The

youngest

was

87

years

old.

Most

were

in

their

nineties;

the

oldest

was

117

years

old.

These

were

the

last

of

Australia's

Muslim

cameleers...

Several

had

subscribed

money

during

the

late

1880s

for

the

construction

of

the

mosque

which

now,

crumbling and decayed, provided their last refuge.”

It

is

only

in

recent

years,

with

the

South

Australian

Museum's

Australian

Muslim

Cameleers

exhibition

(developed

with

support

from

the

Visions

of

Australia

program)

and

book,

that

the

story

and

the

contribution

of

these

pioneers

to

Australia's

history

and

development has been told.

Australia’s Muslim Cameleers exhibition pictures &

dialogue courtesy ABC Alice Springs.

…. CLICK TO VIEW

The above information and more can be accessed on the

Australian Government website

http://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story

/afghan-cameleers